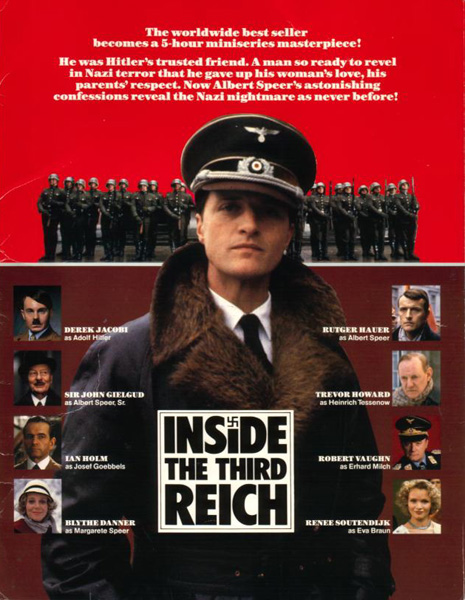

Inside The Third Reich (1982)

CAST:

Rutger Hauer, Blythe Danner, Sir Derek Jacobi, Sir John Gielgud, Sir Ian Holm, Maria Schell, Trevor Howard, Elke Sommer, Stephen Collins, Renée Soutendijk, Randy Quaid, Robert Vaughn, Michael Gough, Maurice Roëves, Derek Newark, David Shawyer, George Murcell, Viveca Lindfors, Zoë Wanamaker

REVIEW:

Inside The Third Reich, a lengthy, critically acclaimed TV miniseries from two-time Emmy winner Marvin J. Chomsky, is a film adaptation of the same-named memoirs by Albert Speer, a bright, cultured German architect who became Adolf Hitler’s personal designer and later Minister of Armaments and War Production, ultimately spending twenty years in Spandau Prison for his use of slave labor to keep the German war effort going, during which time he ostensibly reflected on his errors in judgment and began to write his memoirs. Although forbidden to do so in prison, Speer smuggled them out through a sympathetic guard and formed them into an autobiography upon his release. As one of the few surviving individuals to have had such intimate contact with Hitler, Speer lived well off of book sales until his death shortly before its film adaptation. While many believe Speer to have downplayed his own role in the Third Reich, and criticize the miniseries for not questioning his account, its historical value is undeniable. Inside The Third Reich was filmed on a low budget over a few months of winter in Munich, which is made apparent by the presence of snow in nearly every outdoors scene throughout the miniseries. While the vast scope and detail of Speer’s writings require numerous events to be skipped over, it serves to give the viewer the basics of the workings of the Third Reich.

After the credits play against archive footage of Nazi rallies and death camps (the only onscreen images of the Holocaust in the miniseries), we begin with a young but already notably intelligent Albert Speer (Graham McGrath) growing up during WWI with his upper-class parents (Sir John Gielgud and Maria Schell). Both give fine performances; Gielgud is particularly good as the dignified, aristocratic Albert Sr., a man who may seem somewhat stiff, but is warmer than he may at first appear. As Speer grows up (now played by Dutch actor Rutger Hauer in one of his first international roles) and falls in love with Margarete Weber (Blythe Danner), the anti-Nazi feelings of his father, his friend and mentor Professor Heinrich Tessenow (Trevor Howard), and his new bride Margarete (whose anti-Nazi feelings were pointed out by a Speer biographer as having been exaggerated by the filmmakers) make for an uncomfortable situation when Speer attends a speech by Hitler and likes what he hears.

Several times throughout the miniseries we switch to Speer’s post-war conversations with an American officer (Don Fellows), when Speer is asked one simple question: why? Why did a person such as himself: cultured, intelligent, even in friendly relations with Jewish colleagues, support Adolf Hitler? We see what may be part of the answer upon Speer’s first encounter with the future Führer. Although Speer has professed agreement with Professor Tessenow, who dreads the thought of the Nazis in power, curiosity compels him to go see Hitler for himself. What follows is one of the best sequences in the miniseries, as highly-regarded British actor Sir Derek Jacobi delivers a persuasive speech about the suffering of struggling Germans, starting out in calm, schoolmasterly tones and building into an impassioned harangue against those supposedly responsible for Germany’s woes, including bankers, Communists, and Jews. It is not impossible to see why Speer approves of what he hears and ultimately stands in open support; this is before the Holocaust, before the vast crimes against humanity which made Adolf Hitler a despised name in history, and what he says about the shattered German economy and the plight of German workers is true. By the time he finally, inevitably, lashes out at the Jews, the crowd is already won over.

Speer becomes an active member of the Nazi Party, and things quickly begin to snowball, as he first serves as a chauffeur alongside American-born Nazi supporter Ernst “Putzi” Hanfstaengel (Randy Quaid) and next commissioned by Karl Hanke (a gung-ho Stephen Collins) to construct a Party headquarters building. Speer is excited to have his abilities recognized and appreciated, but the price is the end of his friendship with Tessenow. His increasing success also persuades him to overlook the negative aspects of Nazism- the loss of personal freedoms and the accelerating persecution of the Jews, even when this includes a university colleague. His rise in Nazi circles brings him into contact with Josef Goebbels (Ian Holm), Magda Goebbels (Elke Sommer), Heinrich Himmler (David Shawyer), Hermann Goering (George Murcell), Rudolf Hess (Maurice Roëves), Martin Bormann (Derek Newark), and eventually gains him the personal attention of Hitler himself. At the same time, he is increasingly alienating himself from his father, who deplores his son’s association with what he recognizes from the beginning as a dangerous criminal gang bent on total domination. Feeling removed from the uglier aspects of Hitler’s rule, Speer gladly accompanies him to his mountain retreat where he makes the acquaintance of Eva Braun (Dutch actress Renée Soutendijk). His crowning achievement comes when he presents the Führer with his most magnificent construction: the massive Reich Chancellery. Hitler is delighted, and Speer comes ever more into his esteem and confidence. As Hanfstaengel tells Speer, “you are the nearest thing he has got to a friend”. When war breaks out, Speer is concerned, but continues to throw his support behind the Reich, appointed Minister of Armaments and War Production, in which position he and Field Marshal Milch (Robert Vaughn) keep the war effort going through the use of slave labor. Despite the eager-to-please faithfulness with which he is portrayed by Hauer, Speer is never made to seem as cold-hearted as the other leading Nazis- more an opportunist jumping on the bandwagon than a true fanatical Nazi, he is not entirely comfortable with using slave labor, even if he shoves his misgivings to the back of his mind, does not seem to be personally anti-Semitic, and uses his clout to protect the anti-Nazi Professor Tessenow from the fanatical Dr. Rust (an icy Michael Gough). When Hitler finally declares that Germany be destroyed rather than surrender, a horrified Speer contemplates assassinating him, and travels to the headquarters of German field commanders, persuading them to disobey his scorched-earth orders. Nevertheless, he feels guilty about betraying Hitler’s trust, confessing his actions and shortly thereafter crying upon news of Hitler’s suicide, which he confesses to his American interrogator as the only time he has cried in his life. The Nuremberg Trials are not included onscreen, and the miniseries ends with the aftermath, as Speer is taken away to begin his twenty-year imprisonment.

The miniseries depicts the war and Hitler’s inner circle in a basic, superficial manner, and the extermination of the Jews is not mentioned during the war sequences, only discussed with Speer and the American officer in the post-war prison scenes, when Speer denies any knowledge of it and seems genuinely upset by the death camp footage he was shown during the trials.

The miniseries depicts the war and Hitler’s inner circle in a basic, superficial manner, and the extermination of the Jews is not mentioned during the war sequences, only discussed with Speer and the American officer in the post-war prison scenes, when Speer denies any knowledge of it and seems genuinely upset by the death camp footage he was shown during the trials.

It’s hard to say how much Rutger Hauer’s portrayal reflects the real Albert Speer, as the depiction is based on Speer’s own memoirs which some historians have accused of attempting to downplay and whitewash his own role in the Third Reich. Hauer’s Speer is not fully absolved—among various other things, he turns a blind eye to a Jewish university acquaintance being thrown into a concentration camp—but is never really vilified either, and there’s a misguided earnestness to him. Speer comes across as essentially an idealistic and well-intentioned but ambitious individual, with a passion for architecture but politically and perhaps morally apathetic, who is willing to put unpleasant realities out of his mind because the attraction of fame and success promised by his closeness to Hitler is too strong. Speer partially redeems himself by countermanding Hitler’s orders for the destruction of Germany, an action which undeniably requires the summoning of some backbone, but this act of moral courage is a little late in coming. Among the other members of Hitler’s entourage, easily the best is Ian Holm, whose Dr. Goebbels can veer between charm and fanaticism (his two most memorable moments are a wild-eyed speech presiding over a book burning rally, and an uneasy dinner gathering where he drops a vaguely mobster-esque threat to Speer about there being no place for new entries into Hitler’s inner circle). We see how Goebbels and the others resent Speer’s sudden entry into the circle, but are forced to accept him when he falls under Hitler’s good graces. Apart from Holm’s Goebbels, the other top Nazis don’t get much attention. Derek Newark is adequate as Hitler’s secretary Martin Bormann, who regards Speer as a bitter rival and jealously covets access to the Führer, but Hess, Hanfstaengel, and Hanke leave the stage early on, Himmler (David Shawyer) does little more than stand around in the background, and Goering (Italian actor George Murcell) is never raised above a foppish caricature. Derek Jacobi’s critically-acclaimed, Emmy-winning performance as Hitler is not without its virtues, but in my opinion is overrated and only partially convincing. Jacobi’s resemblance to Hitler is only fair, but he does a good imitation of Hitler’s mannerisms and his vocal patterns, especially in his speech scene. To his credit, Jacobi remains restrained for the most part, never engaging in the wild-eyed maniac approach of too many Hitler portrayers, and attempts to bring a measure of depth and nuance to the role. We see Hitler in banal, day-to-day situations where he seems like a less-than-impressive figure. He loves presiding over dinner gatherings where he can ramble pompously on about his favorite subjects (including the virtues of vegetarianism and his hatred of skiing), or sitting enraptured by a film he has viewed countless times before (his entourage is often obviously bored). But he also shows a sense of humor, entertaining his entourage by doing impressions of other world leaders like Mussolini and Neville Chamberlain, and earns a laugh from Speer and the crowd during the speech scene by poking fun at his own overuse of the word “unshakable”. He has a playful moment with the otherwise often-neglected Eva Braun in the snow at Berchtesgaden. In another moment of rare emotional openness, he confesses to Speer shortly before his death that it will be easy for him to end his own life and be “liberated from this painful existence”. But in the few scenes where he is supposed to throw a fiery Hitlerian tantrum, Jacobi is incapable of projecting menace, and that is a significant failing for any actor playing Hitler. Jacobi’s Hitler comes across as a doddering, rambling dreamer, never as dangerous or fanatical as he should. Since Hitler’s role is so key to the storyline, this is a drawback to the miniseries. In fact, Holm as Goebbels seems far more sinister than Jacobi’s Hitler.

There are a few other failings with the miniseries. We see Speer’s friendship with Eva Braun, played by Renée Soutendijk as a childlike innocent devoted to her Adolf despite the pain he often causes her, but we see little of Magda Goebbels, with whom Speer also had a friendly relationship. Speer’s wife is inaccurately portrayed as vehemently anti-Nazi. The low-budget shoot during winter in Munich means that the outdoors throughout the miniseries continually have a covering of snow, even in scenes set during the summer. The miniseries gives the basic story of Speer’s involvement in the Third Reich, but an interested viewer should by all means read the book, which contains infinitely more material and much more in depth examinations of the principal personalities such as Himmler and Goering. Ultimately the viewer and reader must place themselves in Speer’s shoes and decide for themselves when he should have placed his conscience ahead of his career.

**1/2