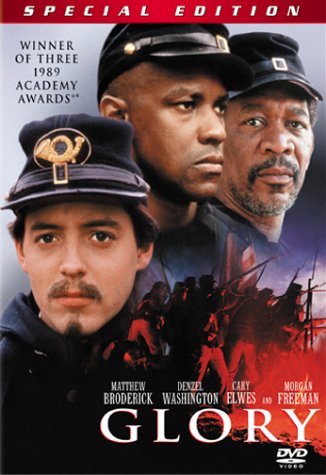

Glory (1989)

DIRECTOR:

Edward Zwick

CAST:

Matthew Broderick, Denzel Washington, Morgan Freeman, Cary Elwes, Andre Braugher, Jihmi Kennedy, Bob Gunton, Cliff De Young

REVIEW:

Perhaps the best Civil War movie ever made- and one of the best war movies period- and a stirring and important historical document, Glory presents the oft-told war between the States from an extremely rarely shown viewpoint- that of freed slaves fighting for the Union (albeit under the command of white officers). Author Kevin Jarre once commented that he hadn’t realized blacks fought in the Civil War until he saw the relief sculpture depicting Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Regiment Memorial in Boston Commons, by August Saint-Gaudens. After this discovery, and the knowledge that many other Americans probably didn’t realize it either, Jarre felt compelled to bring their neglected story to the screen. The main source for the screenplay was the writings of Colonel Shaw himself, which he sent back home to his parents in Massachusetts. Aside from Shaw, the other principal characters are not based on specific individuals, but are composites of various soldiers of the 54th.

Glory begins at the Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest battle in American history, during which we meet Robert Gould Shaw (Matthew Broderick), a young Union officer from a wealthy Boston abolitionist family who reads Emerson and is filled with the idealistic- and not entirely accurate- belief that the Northern objective is to liberate the slaves. Slightly injured at Antietam, Shaw shortly after learns of the Emancipation Proclamation, and that President Lincoln has decided to form a regiment of black soldiers. With the help of his friend Forbes (Cary Elwes), Shaw accepts the position of their commander. The recruits include Shaw’s freeman friend Thomas (Andre Braugher), who soon discovers his comrades do not share his level of culture and education, gravedigger Rawlins (Morgan Freeman), stuttering Jupiter Sharts (Jihmi Kennedy), and tough-as-nails Tripp (Denzel Washington in an Oscar-winning role). For a time, fears that the 54th Massachusetts is to be used only for menial labor seem to come true, but when Shaw finally gets them their chance, his men quickly distinguish themselves in combat. The 54th’s reputation grows, until they are chosen to make a dangerous assault on Fort Wagner in Charleston Harbor.

The first chunk of the film portrays the 54th’s training, and all the inherent problems (not least of which is the reluctance many Union officers have to arm and supply a black regiment), developing the principal recruits- Tripp, Rawlins, Thomas, and Jupiter- into distinct individuals, giving us a sense of their group dynamic, interactions, and personality conflicts, and doing the same for Shaw and Forbes, as the latter does not believe they will ever be allowed into combat and doesn’t bother to properly train them. Shaw is proud of how far the men come in their training, but is uncomfortably aware that they are a separate culture, and feels he does not connect with them as much as he would like. Three pivotal events occur during this sequence. First is when Shaw informs the men of the Confederate decree that any ex slaves caught in battle will be returned to slavery, or executed if caught in uniform. Promising full discharges to all who seek them, Shaw doubtfully returns in the morning to find that the entire regiment is still present, moving their awed commander to utter the words ‘glory, hallelujah’. The second, and probably most indelible scene in the movie is when Tripp is captured as a deserter and Shaw must reluctantly order him whipped, which Tripp endures facing the Colonel in an unflinching stare of defiance. Finally, Shaw wins the men’s respect when they learn they are to be paid less than white soldiers, and joins in when they defiantly tear up their salaries by doing the same with his own. But prejudices still keep the 54th from the combat it thirsts for, and it takes Shaw blackmailing the corrupt General Harker (Bob Gunton) and his lackey Colonel Montgomery (Cliff De Young) to get them into action, where they make a name for themselves, routing a Confederate attack, and then volunteer to lead the assault on Fort Wagner. Throughout, authentic touches are sprinkled in innumerable smaller scenes, such as the shoes issued to the men (they weren’t made in left and right, they were just eventually broken in by your feet), slaves and sharecroppers watching on in awe as black soldiers march proudly past, and the battle scenes populated by hundreds of reenactors. The climactic charge on Fort Wagner is harrowing, and if James Horner’s choir-heavy score gets a little carried away into misty-eyed wax poetic highs, it’s hard not to get swept along.

The performances are uniformly good. Matthew Broderick, at the time best-known for the lightweight teen comedy Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, gives a solid, understated performance as Shaw grows from inexperienced idealist to a demanding but privately insecure commander to finally truly bonding with and being accepted by his men. Unfortunately, memories of Ferris Bueller were still fresh at the time, and Broderick’s worthy dramatic turn was almost unanimously overlooked in the praise showered on Denzel Washington’s Oscar-winning supporting role. Which is not to say that the praise or the Oscar was undeserved. Washington brings fire and raw emotion to the conflicted Tripp, whose hostility hides defensive vulnerability, and supplies Glory’s most indelible moment: his unflinching defiance during the whipping, until one solitary tear escapes to trickle down his stony face. The other standout is Morgan Freeman, who plays the older, wiser Rawlins with sage wisdom, with an impassioned confrontation with Washington being his strongest moment. Cary Elwes, Andre Braugher, and Jihmi Kennedy solidly round out the cast.

Most of the ‘glory’ in Glory is not of the pragmatic variety, but the symbolic. Even the climactic battle achieved little, if anything, militarily, but for the 54th and the thousands of black soldiers who would be inspired by their story to take up the Union flag, it meant everything, both as a validation of Shaw’s earnest and tenacious, often misunderstood and underappreciated efforts, and as a repudiation of the notion, held popularly on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line (a fact sometimes glossed-over, not so here), that blacks were childlike, incompetent, and unreliable. To be sure, attitudes would change slowly enough that the Vietnam War a hundred years later would be the first in which the armed forces were not segregated, but the 54th was a righteous first step.

Most of the ‘glory’ in Glory is not of the pragmatic variety, but the symbolic. Even the climactic battle achieved little, if anything, militarily, but for the 54th and the thousands of black soldiers who would be inspired by their story to take up the Union flag, it meant everything, both as a validation of Shaw’s earnest and tenacious, often misunderstood and underappreciated efforts, and as a repudiation of the notion, held popularly on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line (a fact sometimes glossed-over, not so here), that blacks were childlike, incompetent, and unreliable. To be sure, attitudes would change slowly enough that the Vietnam War a hundred years later would be the first in which the armed forces were not segregated, but the 54th was a righteous first step.

****